Abstract

Background:

Novel treatment strategies are needed to cure disseminated Ewing sarcoma. Primitive neuroectodermal features and a mesenchymal stem cell origin are both compatible with aberrant expression of the ganglioside antigen GD2 and led us to explore GD2 immune targeting in this cancer.

Methods:

We investigated GD2 expression in Ewing sarcoma by immunofluorescence staining. We then assessed the antitumour activity of T cells expressing a chimeric antigen receptor specific for GD2 against Ewing sarcoma in vitro and in vivo.

Results:

Surface GD2 was detected in 10 out of 10 Ewing sarcoma cell lines and 3 out of 3 primary cell cultures. Moreover, diagnostic biopsies from 12 of 14 patients had uniform GD2 expression. T cells specifically modified to express the GD2-specific chimeric receptor 14. G2a-28ζ efficiently interacted with Ewing sarcoma cells, resulting in antigen-specific secretion of cytokines. Moreover, chimeric receptor gene-modified T cells from healthy donors and from a patient exerted potent, GD2-specific cytolytic responses to allogeneic and autologous Ewing sarcoma, including tumour cells grown as multicellular, anchorage-independent spheres. GD2-specific T cells further had activity against Ewing sarcoma xenografts.

Conclusion:

GD2 surface expression is a characteristic of Ewing sarcomas and provides a suitable target antigen for immunotherapeutic strategies to eradicate micrometastatic cells and prevent relapse in high-risk disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The outcome in patients with disseminated Ewing sarcoma remains poor despite intensive multimodal treatment regimens (Ladenstein et al, 2010). The disease often responds well to chemotherapy, but systemic relapses occur in the majority of patients. Targeting of residual disease by novel treatment strategies may sustain remission and improve outcome. In some cancers, tumour antigen-specific antibodies (Coiffier et al, 2010; Yu et al, 2010) or T cells (Dudley et al, 2002) have shown promising activity. Immune targeting of Ewing sarcoma has been limited by the lack of adequate antigens. Although the breakpoint region of the characteristic EWS-FLI1 fusion protein contains unique peptide sequences specifically recognised by T cells (Meyer-Wentrup et al, 2005), clinically tested fusion peptides failed to induce high-avidity T-cell responses (Mackall et al, 2008).

Recent experimental evidence supports either primitive neural crest cells (Coles et al, 2008) or mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (Castillero-Trejo et al, 2005; Riggi et al, 2005; Tirode et al, 2007) as candidate cells of origin for Ewing sarcoma. Both hypotheses can be reconciled by the recent finding that MSCs can arise from neural crest progenitors (Takashima et al, 2007). A shared feature of both neural crest and MSCs is expression of the ganglioside antigen GD2 (Martinez et al, 2007; Xu et al, 2009). Individual reports describe variable levels of GD2 expression on Ewing sarcoma cell lines (Lipinski et al, 1987) and in rare individual primary Ewing sarcoma samples (Cheung et al, 1987; Heiner et al, 1987). A systematic study of GD2 expression in Ewing sarcoma has not yet been performed.

GD2 is a cell-surface molecule with a highly restricted pattern of expression and therefore amenable to targeting by monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and their derivatives. In high-risk neuroblastoma, a highly GD2-expressing malignancy, immunotherapy with a chimeric GD2-specific antibody combined with GM-CSF and IL-2 significantly improved event-free survival (Yu et al, 2010). An alternative strategy is based on the recruitment of T-cell immune responses to GD2 by expression of recombinant chimeric antigen receptors (CARs). Chimeric antigen receptors consist of the antigen-binding domain of a mAb linked to T-cell receptor signalling domains. Chimeric antigen receptor-engineered GD2-specific T cells efficiently interact with GD2-expressing neuroblastoma cells in vitro, resulting in specific tumour cytolysis (Rossig et al, 2001). In a clinical trial in patients with refractory and relapsed disease, GD2-specific T-cell transfer was well tolerated, and first evidence of in vivo persistence and antitumour activity was obtained (Pule et al, 2008; Louis et al, 2011). Here, we hypothesised that GD2 expression may be a common characteristic of Ewing sarcomas and may provide a therapeutic target in this disease.

Material and methods

Cell lines

The identity of all cancer cell lines was confirmed by short tandem repeat profiling (Supplementary Figure S1). The Ewing sarcoma cell lines RD-ES, SK-ES-1, TC-71 and Cado-ES-1 were from DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany). VH-64 cells after multiple and after only 3 in vitro passages (VH-64.P3) following isolation from a malignant pleural effusion, and WE-68 cells were gifts from Frans van Valen's laboratory at the Institute of Experimental Orthopedics of University of Muenster, Germany. These cell lines were characterised by the EuroBoNeT consortium (Ottaviano et al, 2010). A-4573, TC-32, TTC-466, and 5838 were from the cell line bank at Children's Hospital Los Angeles. LAN-1 and LAN-5 (provided by Robert Seeger, Los Angeles, CA, USA), and JF (Malcolm K Brenner, Houston, TX, USA) are human neuroblastoma cell lines. A-204 (DSMZ) is a rhabdomyosarcoma cell line. The packaging cell lines Phoenix-ampho and FLYRD18 were provided by Gary P Nolan (Stanford, CA, USA) and E Vanin (Houston, TX, USA), respectively. Normal human fibroblasts generated from skin biopsies were obtained from Cliona Rooney (Houston, TX, USA). For standard adherent growth, tumour cells were cultured in collagen-coated 25 cm2 tissue culture flasks (VH-64, WE-68, Cado-ES-1, RD-ES, SK-ES-1, TTC-466) or in uncoated flasks (all others) in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; Thermo Fisher, Bonn, Germany) and 2 mM L-glutamine and maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. To generate primary Ewing sarcoma cell cultures, biopsy material from metastatic relapse tumours in two adolescent patients (MS-PES-1, MS-PES-3) was dissected into 1–2 mm fragments, incubated in trypsin (0.05%)/EDTA (0.02%) solution (PAA, Cölbe, Germany), and passed through a cell strainer. Single-cell suspensions were cultured on collagen-coated plates, and adherent cells were re-established in secondary culture.

Patients and tumour samples

Tumour samples were obtained from diagnostic biopsies performed in the Department of Orthopedic Surgery in Muenster in a consecutive cohort of patients treated according to the EURO E.W.I.N.G-99 study protocol. The single selection criterion was availability of frozen samples. Diagnosis was confirmed by immunohistochemistry staining of CD99 and molecular detection of a characteristic fusion transcript (Table 1). Approval for using tumour and/or peripheral blood samples from patients and healthy donors was obtained from the University of Muenster Ethical Board, and informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Constructs

Generation of the GD2-specific CAR 14.G2a-28ζ is described in detail in previous publications from our group (Rossig et al, 2001; Altvater et al, 2006). The receptor contains the single-chain antibody domain of the monoclonal anti-GD2 antibody 14.G2a (Mujoo et al, 1989), the transmembrane domain of CD8α, and the intracellular domains of CD28 and TCRζ. Antigen specificity of 14.G2a CAR gene-modified T cells for GD2 was confirmed in antibody and cold target inhibition assays (Rossig et al, 2001, 2002). A published construct with FMC-63 mAb-derived CD19-specificity was used for comparative experiments (Rossig et al, 2006). Both CAR genes were subcloned into the BamHI and NcoI sites of the retroviral vector SFG (provided by RC Mulligan, Cambridge, MA, USA).

Production of recombinant retrovirus, transduction and expansion of T cells

Fresh retroviral supernatants collected from transiently transfected Phoenix ampho cells were used to infect the packaging cell line FLYRD18, and viral supernatants were generated by adding Isocoves-modified Dulbecco medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% FCS for 24 h of incubation at 32 °C. T cells were nonspecifically prestimulated with CD3- and CD28-specific antibodies and retrovirally transduced with the CAR genes as previously described (Rossig et al, 2001; Altvater et al, 2006).

Flow cytometry

Ewing sarcoma cells were stained with fluorescence-conjugated mAbs directed against GD2 (14G2a; BD Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany), CD166 (mAb 1172, R&D, Wiesbaden, Germany), and CD99 (BD Pharmingen). After fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled 14.G2a mAb became commercially unavailable, further analyses were performed using unlabelled 14.G2a, followed by FITC labelling using secondary goat anti-mouse Ab (both from BD Pharmingen). T cells were analysed using mAbs against CD3, CD8, CD4, and CD56 (BD Pharmingen). Surface expression of 14.G2a-28ζ was determined by staining with a biotinylated goat anti-mouse mAb specific for IgG F(ab’)2 fragment (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cambridgeshire, UK) and secondary phycoerythrin-labelled streptavidin antibody (BD Pharmingen). For each sample, 20 000 cells were analysed with FACS Calibur and BD Cell Quest Software or with FACS Canto and FACS Diva Software. Relative fluorescence intensities (RFI) were calculated by dividing mean fluorescence intensities of mAb-stained cells by those obtained with isotype antibodies or in the absence of antibody.

Immunohistochemistry

Cryostat-frozen tumour sections of 4 μm were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, then permeabilised for 3 h in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.075% Tween and 1% bovine serum albumin. Sections were then incubated overnight with FITC-conjugated 14.G2a mAb, diluted 1 : 50 (2 μg ml–1) in PBS supplemented with 0.01% Tween, and counterstained with DAPI. As controls, cryostat sections of primary neuroblastoma tumours and of pelleted GD2+ and GD2-negative tumour cell lines were stained by immunohistochemistry as above. Stained sections were independently reviewed by two pathologists and compared with a hematoxylin–eosin-stained slide from each case.

Analysis of cytokine production and granzyme B secretion

To assess target-induced cytokine production, T cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells per well in a 24-well plate and stimulated with 1 × 106 irradiated tumour target cells for 6 h. Cytokine secretion was blocked with 10 μg brefeldin A (Sigma, Munich, Germany) per 2 × 106 cells for the final 4 h of co-incubation. Cells were permeabilised using a proprietary solution (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA), and then stained with interferon (IFN)-γ and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α-specific antibodies according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For IFN-γ and granzyme B ELISpot analysis, 10 000 T cells per well were plated in triplicate and stimulated overnight with 50 000 tumour cells per well on Multiscreen 96-well plates (Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany) coated with 10 μg ml–1 anti-IFN-γ Ab or 15 μg ml–1 anti-granzyme B mAb, then incubated with the respective capture antibodies and analysed following the instructions of the human IFN-γ and granzyme B ELISpot kits (both by Mabtech AB, Hamburg, Germany). Spots were counted using an automated reader (CTL ImmunoSpot S5 UV Analyser, CTL Europe, Bonn, Germany).

Cytotoxicity assays

For 51Cr release assays, T effector cells were co-incubated in triplicate with 2500 target cells labelled with 100 μCi51Cr/1 × 106 cells (PE Applied Biosystems; Weiterstadt, Germany) in a total volume of 200 μl in a V-bottomed 96-well plate at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Supernatants were harvested and radioactivity was counted in a gamma counter. Maximum release was determined by target cell lysis with Triton X. For 16-h cytotoxicity experiments, target cells were co-incubated at 1 × 105 cells per well in 96-well plates with various numbers of T cells for 16 h. The percentage of viable tumour cells was determined by co-staining with CD99-, CD3-, and CD45-specific mAbs and subsequent flow cytometry analysis of the relative proportions of cells within the CD99+CD3−CD45− tumour cell gate.

Culture and analysis of spheres

Tumour cells from monolayer cultures were seeded at 2000 cells per well in Ultra-low attachment six-well plates (Costar, Corning, NY, USA). The serum-free sphere culture medium consisted of DMEM/F12 (1 : 1) supplemented with 2% B27 (reagents from Invitrogen), 20 ng ml–1 recombinant human epidermal growth factor (Strathmann Biotech, Hamburg, Germany), 20 ng ml–1 leukaemia inhibitory factor (20 ng ml–1), and 10 IE ml–1 (5 μg ml–1) heparin (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Recombinant human epidermal growth factor was added once on day 4. To assess the sensitivity of spheres to GD2-retargeted T-cell lysis, intact spheres on day 9 were transferred into individual wells of 96-well round bottom plates in sphere culture medium. Maximum perpendicular sphere diameters were quantified using a Zeiss Observer Z1 inverted microscope and Axiovision 4.8 imaging software (Carl Zeiss, Goettingen, Germany) and used to calculate sphere volumes. For each experiment, 27 similar-sized spheres with a volume of ∼200 μm3 were selected and co-incubated with 1000 14.G2a-28ζ T cells or non-transduced T cells per sphere, or in the presence of medium alone for 16 h. Triplicates of three pooled spheres each were used for analysis. Spheres were manually dissociated in an enzyme-free solution containing 1 mM EDTA, 40 mM Tris-HCl and 150 mM NaCl, and viable cells within the tumour cell gate were quantified as above.

Xenogeneic NOD/scid mouse model of Ewing sarcoma

Mouse experiments were approved by the animal care committee of the local government (Bezirksregierung Muenster, Muenster, Germany, Az. 87-51.04.2010.A117). Eight to twelve-week old NOD/scid mice (Charles River Laboratories, Sulzfeld, Germany) were irradiated with a single dose of 3.5 Gy from a linear accelerator 1 day before transplantation to remove residual NK cell activity (Vormoor et al, 2001). A total of 5 × 106 tumour cells were injected subcutaneously into the right flank. Palpable tumours were treated by five intratumoural injections of 1 × 107 14.G2a-28ζ-transduced T cells, or non-transduced T cells as controls each over 2 weeks. Tumour growth was monitored by caliper quantification of diameters.

Statistical analysis

The student t-test was used to test for significance in each set of values, assuming equal variance. Mean values±s.d. are given unless otherwise stated.

Results

GD2 is expressed on the surface of Ewing sarcoma cell lines and primary Ewing sarcoma cells

Surface GD2 expression was detected by flow cytometry using mAb 14. G2a in all Ewing sarcoma cell lines (Figure 1A). In comparison with the RFI of 17.5±0.6 (JF) to 140.7±12.9 (LAN-5) in neuroblastoma cells, expression densities in Ewing sarcoma cells ranged between RFIs of 2.7±2.1 and 52.6±6.2. As expected, primary human fibroblasts and rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines were GD2-negative.

Expression of GD2 on various cell lines and primary tumour cell cultures by flow cytometry. (A) GD2 expression was analysed in various cell lines by flow cytometry after staining with FITC-labelled 14.G2a antibody. According to the surface expression level, cell lines were categorised as highly (GD2high), intermediately (GD2int), and low (GD2low) GD2-expressing cell lines. Controls were unstained and/or isotype-stained cells. The table shows the mean RFI and s.d. of two to four individual experiments. (B) Primary Ewing sarcoma cell cultures established from tumour biopsies upon disseminated Ewing sarcoma relapse in two patients and an early passage of VH-64 were analysed by flow cytometry as above. (C) Surface GD2 expression was directly compared in VH-64 cells after three (P3) and after multiple (Pmultiple) in vitro culture passages, and in MS-PES-1 cells after three (P3) vs six (P6) passages. Standard error bars are derived from three independent experiments performed on individual days.

To exclude that the 14.G2a reactivity of Ewing sarcoma cell lines was due to CD166 rather than GD2 expression, as suggested in one report (Wierzbicki et al, 2008), we performed additional staining experiments with the CD166-specific mAb 1172. CD166high fibroblasts were not reactive with 14.G2a mAb (Supplementary Figure S2). Thus, compatible with a recent report (Agrawal and Frankel, 2010), 14.G2a does not cross-react with surface epitopes of CD166.

To confirm GD2 surface expression in primary Ewing sarcoma cells, we analysed VH-64 cells after only three passages, as well as two cell cultures newly initiated from relapse tumour biopsies (Table 1), (Supplementary Figure S3). GD2 was expressed at variable surface densities on all three early Ewing sarcoma cell cultures (Figure 1B). Surface expression of GD2 was significantly increased in early vs established cultures of VH-64, and the same trend was found in MS-PES-1 cells (Figure 1C).

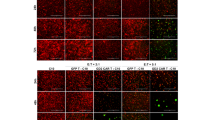

Ultimately, we assessed GD2 expression in cryopreserved tissue sections obtained at primary diagnosis from 14 additional Ewing sarcoma patients (Table 1). Moderate to intense GD2 expression was detected in tumour cells from 12 of the 14 Ewing sarcoma patients by fluorescence microscopy, including patients with localised and metastatic disease (Figure 2C, Table 1). Immunoreactivity had characteristic cell membrane localisation and was restricted to tumour cells, whereas surrounding tissue was negative for GD2. Intensity and pattern of staining was comparable to neuroblastoma tissue sections and to LAN-5 cells (Figure 2). Thus, GD2 expression is a common characteristic of Ewing sarcoma throughout various disease manifestations including localised, disseminated or relapsed disease.

GD2 expression in primary Ewing sarcoma tissue sections by immunofluorescence staining with FITC-labelled 14.G2a antibody (blue fluorescence, DAPI, green fluorescence, 14.G2a). Sections through pelleted A-204 rhabdomyosarcoma cells (A) were used as negative controls, and LAN-5 neuroblastoma cells (A) and primary neuroblastoma tissue sections (B) served as positive controls. Details regarding the individual patients are found in Table 1. (C) Moderate to intense homogeneous cell membrane staining was found in 12 of 14 Ewing sarcoma tumours, as exemplified by tumour samples from six patients.

GD2-specific, CAR-reengineered T cells functionally interact with Ewing sarcoma cells

To investigate whether Ewing sarcoma cells induce antigen-specific activation of GD2-specific T cells, T cell cultures from six healthy donors were gene-modified with the GD2-specific CAR 14.G2a-28ζ (Altvater et al, 2006). As Ewing sarcoma cells are highly sensitive to NK cell lysis in vitro (Verhoeven et al, 2008; Cho et al, 2010), NK cells were removed by magnetic cell selection using CD56-specific microbeads. Retroviral transduction of T cells resulted in 14.G2a-28ζ surface expression in a median of 70.4±9.8 (range 54.9–84.9) T cells. Gene-modified T cell cultures on day 14 consisted of both CD3+CD8+ (47.8±9.0%) and CD3+CD4+ (44.8±13.0%) T cells, whereas CD3-CD56+ NK cells were <1% in all cultures. Co-incubation of 14.G2a-28ζ transduced T cells with the GD2-positive Ewing sarcoma cell lines TC-71 and VH-64, but not the GD2-negative rhabdomyosarcoma cell line A-204 induced production of IFN-γ and TNF-α (Figure 3A). Cytokine production in response to both Ewing sarcoma cell lines was comparable to the neuroblastoma cell line LAN-1 that expresses GD2 at high density and is widely used for preclinical evaluation of GD2-targeting strategies. ELISpot analysis of a wider range of cell lines revealed significant increases of IFN-γ-producing cells in cocultures with both GD2int (TC-71) and GD2low (VH-64, A4573, Cado-ES-1, WE-68) Ewing sarcoma cell lines (Figure 3B).

CAR-transduced, GD2-specific T cells functionally interact with Ewing sarcoma targets. (A) Intracellular production of IFN-γ and TNF-α by non-transduced (top panel) and 14.G2a-28ζ-transduced (bottom panel) T-cell cultures was quantified by flow cytometry in response to 6-h co-incubation with the GD2-negative rhabdomyosarcoma cell line A-204, the GD2high neuroblastoma cell line LAN-1, and the Ewing sarcoma cell lines TC-71 (GD2int) and VH-64 (GD2low), respectively. Shown is one representative experiment of three. (B) IFN-γ release by 14.G2a-28ζ-transduced T cells vs CD19-28ζ- or non-transduced control T cells in response to exposure to LAN-1 positive control and A-204 negative control cells as well as various Ewing sarcoma cell lines was investigated by ELISpot analysis following overnight co-incubation of effector and target cells. Asterisks indicate significant (P<0.05) differences to control. Representative experiment of two.

GD2-specific, CAR-reengineered T cells exert potent cytolytic responses against Ewing sarcoma cells

In a 4-h 51Cr release assay, both VH-64 and TC-71 cells were efficiently lysed by 14.G2a-28ζ-transduced T cells (Figure 4A), and the lower GD2-expressing cell line Cado-ES-1 was also susceptible to lysis, albeit at lower efficiency. Significant granzyme B secretion by 14.G2a-28ζ gene-modified vs non-transduced T cells was found in response to both GD2int (TC-71, TC-32) and GD2low (VH-64, A4573, Cado-ES-1) cell lines, except for the lowest GD2-expressing Ewing sarcoma cell lines WE-68, TTC-466 where responses did not reach statistical significance. With all responsive cell lines, the quantities of response were comparable to those induced by LAN-5, regardless of GD2 expression levels, suggesting a threshold of GD2 expression necessary to trigger cytolytic T-cell responses via CARs (Figure 4B). Background responses of non-transduced T cells or of gene-modifed T cells to the GD2-negative target A-204 were negligible, confirming the specificity of the interaction. We conclude that the level of GD2 expression in many Ewing sarcomas is sufficient to specifically activate T cells and trigger cytolysis by granzyme B secretion via GD2-specific CARs.

CAR-transduced, GD2-specific T cells exert cytolytic responses against allogeneic and autologous Ewing sarcoma targets. (A) Lysis of GD2int (TC-71) and GD2low (VH-64, Cado-ES-1) Ewing sarcoma cells by non-transduced (NT) and 14.G2a-28ζ-transduced T cells in a 51Cr release assay. Representative experiment of three. (B) Granzyme B secretion by 14.G2a-28ζ and non-transduced T cells in response to stimulation with various GD2-expressing target cell lines (see Figure 1 for GD2 expression levels). LAN-1 and A-204 cells served as positive and negative controls, respectively. Representative experiment of two. (C) Lysis of cultured tumour cells from a patient with relapsed Ewing sarcoma by autologous 14.G2a-28ζ and non-transduced T cells in a 4-h 51Cr release assay (left panels), and in a 16-h co-incubation assay by quantification of CD3-negative, CD45-negative, CD99+ tumour cells (right panel). Autologous cells after either three (MS-PES-1.P3) or six (MS-PES-1.P6) passages were used as targets in the 51Cr-release assay, and MS-PES-1.P6 cells were used for the 16-h co-incubation assay. Shown is one representative experiment of two. Asterisks indicate significant (P<0.05) differences to control.

GD2-redirected T cells from Ewing sarcoma patients efficiently lyse autologous tumour cells

Translation of these findings into novel, GD2-based treatment strategies relies on the sensitivity of primary Ewing sarcoma cells to GD2 targeting and on the capacity of T cells obtained from sarcoma patients to mediate antitumour responses. Therefore, we performed autologous co-incubation experiments of short-term-cultured Ewing sarcoma cells from a relapse biopsy with 14.G2a-28ζ-transduced T cells, generated from peripheral blood after recovery of blood counts from chemotherapy. 14.G2a-28ζ transduced T cells efficiently lysed autologous Ewing sarcoma cells (Figure 4C). Remarkably, lysis of early passages of tumour cells was significantly higher compared with cells maintained in culture for further three passages. This observation is in line with the higher GD2 expression in early passages of cultured lines (Figure 1C) and the strong GD2 expression by immunohistochemistry in the majority of Ewing sarcoma tissue sections (Figure 2). In 16-h cocultures with autologous gene-modified T cells at 1 : 1 and 0.5 : 1 effector-to-target cell ratios, primary Ewing sarcoma cells were efficiently eliminated (Figure 4C). Thus, despite intensive cytotoxic pretreatment, functional GD2-specific T cells were efficiently generated from an Ewing sarcoma patient and potently and specifically eliminated autologous tumour cells in vitro, confirming the clinical feasibility of GD2 targeting.

GD2-redirected T cells efficiently lyse Ewing sarcoma cells grown as spheres under anchorage-independent conditions

As monolayer cultures of Ewing sarcoma cells inadequately reflect the three-dimensional, anchorage-independent in vivo growth of tumour micrometastases (Lawlor et al, 2002), further experiments were performed in a sphere culture model. Ewing sarcoma sphere growth under restricted serum conditions has recently been shown to select for cells that possess higher tumourigenicity (Wahl et al, 2010). Moreover, we found that Ewing sarcoma spheres under these conditions are more resistant to chemotherapy than single-cell suspensions (Leuchte et al, unpublished data). Sixteen-hour cocultures of Ewing sarcoma spheres with GD2-retargeted T cells resulted in efficient lysis, whereas non-transduced T cells had no visible effect on sphere structure (Figure 5).

CAR-transduced, GD2-specific T cells efficiently lyse multicellular Ewing sarcoma spheres. Similar-sized VH-64 spheres of 200–250 μm, reflecting about 1000 cells (Leuchte et al, manuscript in preparation) were co-incubated with 1000 14.G2a-28ζ T cells or non-transduced T cells per sphere, or in the presence of medium alone. Triplicates (shown in rows) of three pooled spheres each were used for analysis. The top panel shows photos of spheres following 16 h co-incubation. Spheres were then dissociated and stained with CD99-, CD3- and CD45-specific mAbs, followed by quantification of viable cells within the tumour cell gate by flow cytometry (bottom panel).

In vivo antitumour activity of GD2-retargeted T cells against established tumour xenografts

To demonstrate the therapeutic efficacy of adoptively transferred 14.G2a-28ζ T cells, cohorts of 10 NOD/scid mice were subcutaneously injected with 5 × 106 VH-64 cells per mouse. Upon detection of palpable tumours, five doses of 1x107 gene-modified, GD2-specific T cells each were injected intratumourally over a period of 2 weeks. Control mice received analogous injections of non-transduced T cells. The analytic endpoint was relative tumour growth (in %). Mean tumour volumes at first injection of T cells were not significantly different between controls and 14.G2a-28ζ-treated mice (63.5±21.0 mm3 vs 82.6±38.0 mm3, P=0.40). Although tumours in mice receiving injections of non-transduced T cells continued to grow, 14.G2a-28ζ T cells efficiently and significantly reduced further tumour growth (Figure 6). Immunohistochemistry analysis of tumours removed from both 14.G2a-28ζ T cell-treated and control mice did not reveal any significant differences in GD2 expression (Supplementary Figure S4), arguing against either downregulation of GD2 or negative selection of GD2-negative or GD2low cells under antigen-specific T-cell therapy. We further established an advanced vivo model that recapitulates the major aspects of the growth and progression pattern of disseminated Ewing sarcoma (Vormoor et al, 2001); however, unreliable engraftment of low cell numbers and highly heterogenous disease manifestations among mice intravenously injected with VH-64 cells impeded objective analysis of therapeutic effects.

In vivo activity of 14.G2a-28ζ T cells against solid tumour xenografts. A cohort of 10 irradiated (3.5 Gy) NOD-scid mice were subcutaneously injected with 5 × 106 VH-64 cells/mouse. Upon detection of palpable tumours, 5 doses of 1 × 107 gene-modified, 14.G2a-28ζ T cells each were injected intratumourally over a period of 2 weeks (arrows). Control mice received analogous injections of non-transduced T cells. The analytic endpoint was relative tumour growth (in %), and was determined by dividing the tumour volume (mm3) at time of analysis by the initial tumour volume at onset of T-cell therapy (mm3) ( × 100).

Despite the limitations of our solid tumour model, the in vivo data demonstrate that the antitumour activity of GD2-retargeted T cells in Ewing sarcoma extends beyond single-cell suspensions and monolayers to both multicellular spheres and in vivo solid tumours.

Discussion

The glycosphingolipid GD2 is an attractive target antigen for immunotherapy, as expression in normal tissues is highly restricted (Schulz et al, 1984). Moreover, GD2 is postulated to have a role in (tumour) cell adherence to the extracellular matrix (Cheresh et al, 1986) and may thus be involved in the local aggressive and metastatic phenotype of solid tumours. The prototype GD2+ malignancy is neuroblastoma, a paediatric solid tumour deriving from the sympathetic nervous system. Recent clinical phase II and III studies with GD2-specific mAbs (Yu et al, 2010), immunoconjugates (Shusterman et al, 2010) or retargeted T cells (Pule et al, 2008; Louis et al, 2011) have shown antitumour activity in high-risk neuroblastoma and are now starting to make an impact on the management of this disease.

Here, we provide evidence that Ewing sarcoma may be another candidate for GD2-targeting strategies. Although expression of GD2 in malignancies other than neuroblastoma, including melanoma (Tsuchida et al, 1989) as well as a proportion of high- and low-grade (non-Ewing) sarcomas (Chang et al, 1992; Modak et al, 2002), is not a novel finding, published data in Ewing sarcoma are limited. One study reports GD2 expression at low to moderate levels in 10 Ewing sarcoma cell lines (Lipinski et al, 1987), whereas another cell line was found negative (Schulz et al, 1984). In an analysis focussing on osteosarcoma, 2 of 4 Ewing sarcoma samples were GD2-positive (Heiner et al, 1987), and a primary Ewing sarcoma passaged in nude mice was reported to express GD2 (Cheung et al, 1987). Here, we substantially and systematically extend these findings and identify GD2 expression as a common feature of Ewing sarcomas including established cell lines, low-passage cell cultures, and primary biopsies. GD2 expression in Ewing sarcoma is compatible with the presumed cellular origin of the disease from either primitive neuroectodermal cells (Coles et al, 2008) or bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells (Tirode et al, 2007), as both cell types express GD2 (Martinez et al, 2007).

GD2 expression in Ewing sarcomas was clearly not restricted to localised tumours or to primary diagnosis. These observations are in line with findings in neuroblastoma where GD2 is a reliable marker of disease throughout all stages and with consistent expression at relapse (Kramer et al, 1998). Future studies including large numbers of Ewing sarcoma patients should address the prognostic significance of GD2 expression status and include longitudinal analysis at both diagnosis and relapse. As GD2 surface expression is undetectable after paraffin-embedding of tumour tissue, cryopreserved material has to be systematically collected for these analyses.

From a clinical point of view, identification of GD2 as a reliable marker of Ewing sarcoma opens new avenues for therapeutic targeting. Here, we show that GD2-retargeted T cells efficiently interact with Ewing sarcoma cells and lyse tumour cells both in vitro and in vivo. Although Ewing sarcoma sphere structures were recently shown to provide resistance against cellular immune targeting by NK cells (Holmes et al, 2011), in vitro sensitivity to GD2-mediated T-cell lysis included multicellular sphere cultures grown under restricted serum conditions, modelling micrometastatic tumour growth. Moreover, evidence for an antitumour activity of GD2-specific T cells against larger and vascularised tumours was obtained in vivo. Thus, our findings strongly support translational application of GD2-targeted therapies in Ewing sarcoma.

Despite the low GD2 expression densities in many cell lines, the functional data presented here support effective interaction of a majority of Ewing sarcomas with GD2-redirected T cells. Interestingly, direct comparisons between early and later passages of two individual cell lines suggest some degree of downregulation of GD2 expression during prolonged in vitro culture. This observation, that has to be substantiated in a larger number of samples, may explain the discrepancy between the relatively high in situ expression of GD2 compared with established cell lines and further encourages therapeutic targeting of GD2 in Ewing sarcoma. A potential explanation is that differentiation-inducing agents present within the serum-containing culture medium may affect GD2 expression via transcriptional and/or epigenetic regulation of enzymes involved in ganglioside metabolism (Suzuki et al, 2011). The concern remains that subsets of GD2-negative tumour cells are present within Ewing sarcomas and may be selected for further tumour growth during GD2-targeted therapy. Besides clinical evaluation of GD2 targeting in Ewing sarcoma, elucidation of the significance of GD2 expression for the malignant phenotype of Ewing sarcoma will help to resolve the stability of this marker and its therapeutic usefulness.

As a carbohydrate antigen, GD2 is not presented to T cells by MHC class I. T cell targeting of GD2 has become possible by the CAR strategy that extends the target range of T cells to non-protein antigens (Rossig et al, 2001) and also bypasses the failure of many Ewing sarcomas to express HLA class I molecules (Berghuis et al, 2009). Over antibody targeting, T-cell-based approaches have several potential advantages. Firstly, T cells may establish an antigen-specific immune memory and provide long-lasting anti-tumour immune control (Dudley et al, 2002; Morgan et al, 2006; Bollard et al, 2007; Pule et al, 2008). Secondly, GD2-specific CARs lack the antibody Fc domain that is considered responsible for complement-dependent toxicities, including the neuropathic pain syndrome (Sorkin et al, 2010). Indeed, adoptive immunotherapy with 14.G2aζ-transduced T cells was safe and well-tolerated in a first phase I study in neuroblastoma patients (Pule et al, 2008; Louis et al, 2011). Thirdly, CAR-reengineered T cells may overcome the limited avidity of mAbs against targets expressing low levels of antigen. The optimised design of current tumour-specific CARs and effective gene transfer techniques indeed enable responses to antigenlow targets (Ahmed et al, 2009; Yvon et al, 2009). As a consequence of the limited persistence, homing and antitumour function of CAR gene-engineered T cells in early clinical studies, current strategies focus on generating cells with robust capacity to expand, persist, and migrate to the tumour, and on delivering them into a supportive immune milieu. Some recent clinical studies have indeed demonstrated clinically significant antitumour activity of therapeutic T cells (Louis et al, 2011; Porter et al, 2011). One efficient means to improve expansion and persistence of transferred T cells appears to be the elimination of regulatory T cells by previous lymphodepleting chemotherapy (Dudley et al, 2002; Rapoport et al, 2011). In Ewing sarcoma, this can be achieved by applying T-cell therapy in the context of lymphopenia after high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue. Theoretically, off-target effects with GD2-positive normal bone marrow MSCs may interfere with haematopoietic stem cell engraftment in this context; however, no haematological toxicity was observed in any clinical trial in patients receiving GD2 mAbs or conjugates (Shusterman et al, 2010; Yu et al, 2010) or GD2-reengineered T cells (Pule et al, 2008). Increasing knowledge regarding local and systemic mechanisms of immune escape (Berghuis et al, 2011; Holmes et al, 2011) will further help to optimise integration of immunotherapies into the treatment of Ewing sarcoma.

In summary, this report extends the promise of GD2 targeting to the treatment of Ewing sarcoma. GD2-targeted immunotherapy may be a potent strategy to control or eliminate residual disease in patients with recurrent or refractory Ewing sarcoma.

Change history

28 March 2012

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Agrawal V, Frankel AE ( 2010 ) 14G2a anti-GD2 crossreactivity with the CD166 antigen . J Immunother 33 : 1014 – 1015

Ahmed N, Salsman VS, Yvon E, Louis CU, Perlaky L, Wels WS, Dishop MK, Kleinerman EE, Pule M, Rooney CM, Heslop HE, Gottschalk S ( 2009 ) Immunotherapy for osteosarcoma: genetic modification of T cells overcomes low levels of tumor antigen expression . Mol Ther 17 : 1779 – 1787

Altvater B, Pscherer S, Landmeier S, Niggemeier V, Juergens H, Vormoor J, Rossig C ( 2006 ) CD28 co-stimulation via tumour-specific chimaeric receptors induces an incomplete activation response in Epstein-Barr virus-specific effector memory T cells . Clin Exp Immunol 144 : 447 – 457

Berghuis D, de Hooge AS, Santos SJ, Horst D, Wiertz EJ, van Eggermond MC, van den Elsen PJ, Taminiau AH, Ottaviano L, Schaefer KL, Dirksen U, Hooijberg E, Mulder A, Melief CJ, Egeler RM, Schilham MW, Jordanova ES, Hogendoorn PC, Lankester AC ( 2009 ) Reduced human leukocyte antigen expression in advanced-stage Ewing sarcoma: implications for immune recognition . J Pathol 218 : 222 – 231

Berghuis D, Santos SJ, Baelde HJ, Taminiau AH, Egeler RM, Schilham MW, Hogendoorn PC, Lankester AC ( 2011 ) Pro-inflammatory chemokine-chemokine receptor interactions within the Ewing sarcoma microenvironment determine CD8 (+) T-lymphocyte infiltration and affect tumour progression . J Pathol 223 : 347 – 357

Bollard CM, Gottschalk S, Leen AM, Weiss H, Straathof KC, Carrum G, Khalil M, Wu MF, Huls MH, Chang CC, Gresik MV, Gee AP, Brenner MK, Rooney CM, Heslop HE ( 2007 ) Complete responses of relapsed lymphoma following genetic modification of tumor-antigen presenting cells and T-lymphocyte transfer . Blood 110 : 2838 – 2845

Castillero-Trejo Y, Eliazer S, Xiang L, Richardson JA, Ilaria Jr RL ( 2005 ) Expression of the EWS/FLI-1 oncogene in murine primary bone-derived cells Results in EWS/FLI-1-dependent, ewing sarcoma-like tumors . Cancer Res 65 : 8698 – 8705

Chang HR, Cordon-Cardo C, Houghton AN, Cheung NK, Brennan MF ( 1992 ) Expression of disialogangliosides GD2 and GD3 on human soft tissue sarcomas . Cancer 70 : 633 – 638

Cheresh DA, Pierschbacher MD, Herzig MA, Mujoo K ( 1986 ) Disialogangliosides GD2 and GD3 are involved in the attachment of human melanoma and neuroblastoma cells to extracellular matrix proteins . J Cell Biol 102 : 688 – 696

Cheung NKV, Neely JE, Landmeier B, Nelson D, Miraldi F ( 1987 ) Targeting of Ganglioside-Gd2 Monoclonal-Antibody to Neuroblastoma . J Nucl Med 28 : 1577 – 1583

Cho D, Shook DR, Shimasaki N, Chang YH, Fujisaki H, Campana D ( 2010 ) Cytotoxicity of activated natural killer cells against pediatric solid tumors . Clin Cancer Res 16 : 3901 – 3909

Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den NE, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, Lefort S, Marit G, Macro M, Sebban C, Belhadj K, Bordessoule D, Ferme C, Tilly H ( 2010 ) Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte . Blood 116 : 2040 – 2045

Coles EG, Lawlor ER, Bronner-Fraser M ( 2008 ) EWS-FLI1 causes neuroepithelial defects and abrogates emigration of neural crest stem cells . Stem Cells 26 : 2237 – 2244

Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, Yang JC, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Sherry R, Restifo NP, Hubicki AM, Robinson MR, Raffeld M, Duray P, Seipp CA, Rogers-Freezer L, Morton KE, Mavroukakis SA, White DE, Rosenberg SA ( 2002 ) Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes . Science 298 : 850 – 854

Heiner JP, Miraldi F, Kallick S, Makley J, Neely J, Smithmensah WH, Cheung NKV ( 1987 ) Localization of Gd2-specific monoclonal-antibody 3F8 in human osteosarcoma . Cancer Res 47 : 5377 – 5381

Holmes TD, El Sherbiny YM, Davison A, Clough SL, Blair GE, Cook GP ( 2011 ) A human NK cell activation/inhibition threshold allows small changes in the target cell surface phenotype to dramatically alter susceptibility to NK cells . J Immunol 186 : 1538 – 1545

Kramer K, Gerald WL, Kushner BH, Larson SM, Hameed M, Cheung NK ( 1998 ) Disialoganglioside G (D2) loss following monoclonal antibody therapy is rare in neuroblastoma . Clin Cancer Res 4 : 2135 – 2139

Ladenstein R, Potschger U, Le Deley MC, Whelan J, Paulussen M, Oberlin O, van den BH, Dirksen U, Hjorth L, Michon J, Lewis I, Craft A, Jurgens H ( 2010 ) Primary disseminated multifocal Ewing sarcoma: results of the Euro-EWING 99 trial . J Clin Oncol 28 : 3284 – 3291

Lawlor ER, Scheel C, Irving J, Sorensen PH ( 2002 ) Anchorage-independent multi-cellular spheroids as an in vitro model of growth signaling in Ewing tumors . Oncogene 21 : 307 – 318

Lipinski M, Braham K, Philip I, Wiels J, Philip T, Goridis C, Lenoir GM, Tursz T ( 1987 ) Neuroectoderm-associated antigens on Ewing's sarcoma cell lines . Cancer Res 47 : 183 – 187

Louis CU, Savoldo B, Dotti G, Pule M, Yvon E, Myers GD, Rossig C, Russell HV, Diouf O, Liu E, Liu H, Wu MF, Gee AP, Mei Z, Rooney CM, Heslop HE, Brenner MK ( 2011 ) Anti-tumor activity and long-term fate of chimeric antigen receptor positive T-cells in patients with neuroblastoma . Blood 118 (23) : 6050 – 6056

Mackall CL, Rhee EH, Read EJ, Khuu HM, Leitman SF, Bernstein D, Tesso M, Long LM, Grindler D, Merino M, Kopp W, Tsokos M, Berzofsky JA, Helman LJ ( 2008 ) A pilot study of consolidative immunotherapy in patients with high-risk pediatric sarcomas . Clin Cancer Res 14 : 4850 – 4858

Martinez C, Hofmann TJ, Marino R, Dominici M, Horwitz EM ( 2007 ) Human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells express the neural ganglioside GD2: a novel surface marker for the identification of MSCs . Blood 109 : 4245 – 4248

Meyer-Wentrup F, Richter G, Burdach S ( 2005 ) Identification of an immunogenic EWS-FLI1-derived HLA-DR-restricted T helper cell epitope . Pediatr Hematol Oncol 22 : 297 – 308

Modak S, Gerald W, Cheung NK ( 2002 ) Disialoganglioside GD2 and a novel tumor antigen: potential targets for immunotherapy of desmoplastic small round cell tumor . Med Pediatr Oncol 39 : 547 – 551

Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Hughes MS, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Topalian SL, Kammula US, Restifo NP, Zheng ZL, Nahvi A, de Vries CR, Rogers-Freezer LJ, Mavroukakis SA, Rosenberg SA ( 2006 ) Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes . Science 314 : 126 – 129

Mujoo K, Kipps TJ, Yang HM, Cheresh DA, Wargalla U, Sander DJ, Reisfeld RA ( 1989 ) Functional properties and effect on growth suppression of human neuroblastoma tumors by isotype switch variants of monoclonal antiganglioside GD2 antibody 14.18 . Cancer Res 49 : 2857 – 2861

Ottaviano L, Schaefer KL, Gajewski M, Huckenbeck W, Baldus S, Rogel U, Mackintosh C, de Alava E, Myklebost O, Kresse SH, Meza-Zepeda LA, Serra M, Cleton-Jansen AM, Hogendoorn PC, Buerger H, Aigner T, Gabbert HE, Poremba C ( 2010 ) Molecular characterization of commonly used cell lines for bone tumor research: a trans-European EuroBoNet effort . Genes Chromosomes Cancer 49 : 40 – 51

Porter DL, Levine BL, Kalos M, Bagg A, June CH ( 2011 ) Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia . N Engl J Med 365 : 725 – 733

Pule MA, Savoldo B, Myers GD, Rossig C, Russell HV, Dotti G, Huls MH, Liu EL, Gee AP, Mei Z, Yvon E, Weiss HL, Liu H, Rooney CM, Heslop HE, Brenner MK ( 2008 ) Virus-specific T cells engineered to coexpress tumor-specific receptors: persistence and antitumor activity in individuals with neuroblastoma . Nat Med 14 : 1264 – 1270

Rapoport AP, Aqui NA, Stadtmauer EA, Vogl DT, Fang HB, Cai L, Janofsky S, Chew A, Storek J, Akpek G, Badros A, Yanovich S, Tan MT, Veloso E, Pasetti MF, Cross A, Philip S, Murphy H, Bhagat R, Zheng Z, Milliron T, Cotte J, Cannon A, Levine BL, Vonderheide RH, June CH ( 2011 ) Combination immunotherapy using adoptive T-cell transfer and tumor antigen vaccination on the basis of hTERT and survivin after ASCT for myeloma . Blood 117 : 788 – 797

Riggi N, Cironi L, Provero P, Suva ML, Kaloulis K, Garcia-Echeverria C, Hoffmann F, Trumpp A, Stamenkovic I ( 2005 ) Development of Ewing's sarcoma from primary bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells . Cancer Res 65 : 11459 – 11468

Rossig C, Bar A, Pscherer S, Altvater B, Pule M, Rooney CM, Brenner MK, Jurgens H, Vormoor J ( 2006 ) Target antigen expression on a professional antigen-presenting cell induces superior proliferative antitumor T-cell responses via chimeric T-cell receptors . J Immunother 29 : 21 – 31

Rossig C, Bollard CM, Nuchtern JG, Merchant DA, Brenner MK ( 2001 ) Targeting of G (D2)-positive tumor cells by human T lymphocytes engineered to express chimeric T-cell receptor genes . Int J Cancer 94 : 228 – 236

Rossig C, Bollard CM, Nuchtern JG, Rooney CM, Brenner MK ( 2002 ) Epstein-Barr virus-specific human T lymphocytes expressing antitumor chimeric T-cell receptors: potential for improved immunotherapy . Blood 99 : 2009 – 2016

Schulz G, Cheresh DA, Varki NM, Yu A, Staffileno LK, Reisfeld RA ( 1984 ) Detection of ganglioside GD2 in tumor tissues and sera of neuroblastoma patients . Cancer Res 44 : 5914 – 5920

Shusterman S, London WB, Gillies SD, Hank JA, Voss SD, Seeger RC, Reynolds CP, Kimball J, Albertini MR, Wagner B, Gan J, Eickhoff J, DeSantes KB, Cohn SL, Hecht T, Gadbaw B, Reisfeld RA, Maris JM, Sondel PM ( 2010 ) Antitumor activity of hu14.18-IL2 in patients with relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma: a Children's Oncology Group (COG) phase II study . J Clin Oncol 28 : 4969 – 4975

Sorkin LS, Otto M, Baldwin III WM, Vail E, Gillies SD, Handgretinger R, Barfield RC, Ming YH, Yu AL ( 2010 ) Anti-GD (2) with an FC point mutation reduces complement fixation and decreases antibody-induced allodynia . Pain 149 : 135 – 142

Suzuki Y, Yanagisawa M, Ariga T, Yu RK ( 2011 ) Histone acetylation-mediated glycosyltransferase gene regulation in mouse brain during development . J Neurochem 116 : 874 – 880

Takashima Y, Era T, Nakao K, Kondo S, Kasuga M, Smith AG, Nishikawa S ( 2007 ) Neuroepithelial cells supply an initial transient wave of MSC differentiation . Cell 129 : 1377 – 1388

Tirode F, Laud-Duval K, Prieur A, Delorme B, Charbord P, Delattre O ( 2007 ) Mesenchymal stem cell features of Ewing tumors . Cancer Cell 11 : 421 – 429

Tsuchida T, Saxton RE, Morton DL, Irie RF ( 1989 ) Gangliosides of human melanoma . Cancer 63 : 1166 – 1174

Verhoeven DH, de Hooge AS, Mooiman EC, Santos SJ, ten Dam MM, Gelderblom H, Melief CJ, Hogendoorn PC, Egeler RM, van Tol MJ, Schilham MW, Lankester AC ( 2008 ) NK cells recognize and lyse Ewing sarcoma cells through NKG2D and DNAM-1 receptor dependent pathways . Mol Immunol 45 : 3917 – 3925

Vormoor J, Baersch G, Decker S, Hotfilder M, Schafer KL, Pelken L, Rube C, Van Valen F, Jurgens H, Dockhorn-Dworniczak B ( 2001 ) Establishment of an in vivo model for pediatric Ewing tumors by transplantation into NOD/scid mice . Pediatr Res 49 : 332 – 341

Wahl J, Bogatyreva L, Boukamp P, Rojewski M, Van Valen F, Fiedler J, Hipp N, Debatin KM, Beltinger C ( 2010 ) Ewing's sarcoma cells with CD57-associated increase of tumorigenicity and with neural crest-like differentiation capacity . Int J Cancer 127 : 1295 – 1307

Wierzbicki A, Gil M, Ciesielski M, Fenstermaker RA, Kaneko Y, Rokita H, Lau JT, Kozbor D ( 2008 ) Immunization with a mimotope of GD2 ganglioside induces CD8+ T cells that recognize cell adhesion molecules on tumor cells . J Immunol 181 : 6644 – 6653

Xu J, Liao W, Gu D, Liang L, Liu M, Du W, Liu P, Zhang L, Lu S, Dong C, Zhou B, Han Z ( 2009 ) Neural ganglioside GD2 identifies a subpopulation of mesenchymal stem cells in umbilical cord . Cell Physiol Biochem 23 : 415 – 424

Yu AL, Gilman AL, Ozkaynak MF, London WB, Kreissman SG, Chen HX, Smith M, Anderson B, Villablanca JG, Matthay KK, Shimada H, Grupp SA, Seeger R, Reynolds CP, Buxton A, Reisfeld RA, Gillies SD, Cohn SL, Maris JM, Sondel PM ( 2010 ) Anti-GD2 antibody with GM-CSF, interleukin-2, and isotretinoin for neuroblastoma . N Engl J Med 363 : 1324 – 1334

Yvon E, Del Vecchio M, Savoldo B, Hoyos V, Dutour A, Anichini A, Dotti G, Brenner MK ( 2009 ) Immunotherapy of metastatic melanoma using genetically engineered GD2-specific T cells . Clin Cancer Res 15 : 5852 – 5860

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant #109566 by Deutsche Krebshilfe (to CR), by a grant by the University of Muenster Faculty of Medicine ‘Innovative Medizinische Forschung (IMF)’ program (to CR), and EU funding provided for the ‘CHILDHOPE’ network program under the terms of an EU Framework 6 grant (to CR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kailayangiri, S., Altvater, B., Meltzer, J. et al. The ganglioside antigen GD2 is surface-expressed in Ewing sarcoma and allows for MHC-independent immune targeting. Br J Cancer 106, 1123–1133 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.57

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.57

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

CAR T cells as micropharmacies against solid cancers: Combining effector T-cell mediated cell death with vascular targeting in a one-step engineering process

Cancer Gene Therapy (2023)

-

Emerging phagocytosis checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2023)

-

Neomorphic DNA-binding enables tumor-specific therapeutic gene expression in fusion-addicted childhood sarcoma

Molecular Cancer (2022)

-

Chimeric Antigen Receptor-modified T cells targeting EphA2 for the immunotherapy of paediatric bone tumours

Cancer Gene Therapy (2021)

-

Anti-GD2/4-1BB chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for the treatment of Chinese melanoma patients

Journal of Hematology & Oncology (2018)