Published online Apr 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4373

Peer-review started: August 20, 2014

First decision: September 27, 2014

Revised: October 22, 2014

Accepted: December 16, 2014

Article in press: December 16, 2014

Published online: April 14, 2015

Although ipilimumab has been shown to improve survival in patients with metastatic melanoma and cause regression of metastatic renal cell carcinoma, the associated immune-related toxicities are of concern. The resultant T cell activation by this monoclonal antibody causes an increased immune response, which has been associated with many immune-regulated adverse effects. One of the most concerning effects is the development of colitis. Upwards to 8% of patients have been reported to develop colitis, with 5% being severe (Grades 3-4). While initial treatment of such adverse effects is generally comprised of supportive and symptomatic treatment, more severe cases warrant the use of high dose steroids. Furthermore, use of anti-TNF agents is usually reserved for those cases that prove to be refractory to steroids. We describe a systematic case review of seven patients who developed gastrointestinal symptoms following initiation of ipilimumab immunotherapy, and present the steps in their evaluation, treatment and outcomes at our institution.

Core tip: The development of colitis in the setting of ipilimumab use has become of great concern. Treatment regimens, predictive factors, and prognostic indicators have yet to become standardized and elucidated. Here we present one of the largest case series of ipilimumab associated colitis at a single tertiary care institution, as well as our approach to evaluating and treating suspected cases.

- Citation: Rastogi P, Sultan M, Charabaty AJ, Atkins MB, Mattar MC. Ipilimumab associated colitis: An IpiColitis case series at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(14): 4373-4378

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i14/4373.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4373

Although ipilimumab has been shown to improve survival in patients with metastatic melanoma and cause regression of metastatic renal cell carcinoma, the associated immune-related toxicities are of concern[1,2]. The resultant T cell activation by this monoclonal antibody causes an increased immune response, which has been associated with many immune-regulated adverse effects. One of the most concerning effects is the development of colitis. Upwards to 8% of patients have been reported to develop colitis, with 5% being severe (Grades 3-4). While initial treatment of such adverse effects is generally comprised of supportive and symptomatic treatment, more severe cases warrant the use of high dose steroids. Furthermore, use of anti-TNF agents is usually reserved for those cases that prove to be steroid resistant[3].

In March 2011, ipilimumab was approved for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. This monoclonal antibody blocks inhibition of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) causing T cell activation and proliferation, preventing tumor evasion. The resulting immune up-regulation has been associated with numerous immune-regulated adverse effects (irAEs) including colitis, dermatitis, hepatitis, and hypophysitis. Fatigue, weight loss, and electrolyte imbalances encompass the clinical manifestations of severe diarrhea, which can progress to colitis, and in the worst case, bowel perforation. Up to 46% of patients will experience such gastrointestinal toxicities after 7 wk of therapy[4]. Severity of diarrheal symptoms are graded based on the Common Terminology for Adverse Events (CTAE)[5], and further characterized as mild to moderate (Grades 1-2) or severe (Grades 3-4). Symptomatic management with loperamide is indicated for mild cases. If symptoms persist or become severe, initiation of steroid therapy is indicated along with endoscopy to assess for colitis. High dose steroids are used in severe cases, and infliximab being reserved for steroid resistant cases[6]. Here we report our experience in the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal irAEs in our patients receiving ipilimumab.

A retrospective analysis was conducted to identify those patients who developed gastrointestinal symptoms in the setting of receiving ipilimumab treatment from December 2012 to December 2013. A total of 19 patients were identified as receiving ipilimumab as part of their infusion protocols. Seven cases were identified as having gastrointestinal symptoms warranting inpatient hospital evaluation. Of the 7 cases reviewed (four male, three female) a mean age of 58 years (range, 38-71 years) and diarrheal symptoms ranging from mild to severe (Grades 1-4) was noted. Below we present detailed descriptions of each of the seven cases and a summation presented in Table 1.

| No. | Age (yr) | Gender | Diagnosis | Symptom grade | Symptom onset | CRP levels (Normal 0-3 mg/L) |

| Case 1 | 63 | Female | Nasal Mucosa Melanoma | 3 → 4 | 6 wk | 108 |

| Case 2 | 38 | Male | Back Skin Melanoma | 1 → 2 | 4 wk | 137 |

| Case 3 | 71 | Female | Facial Melanoma | 2 → 4 | 5 wk | 38.3 (< 2.9 ten days after first infliximab infusion) |

| Case 4 | 44 | Female | Right Inguinal Melanoma | 3 | 9 wk | 55.7 |

| Case 5 | 66 | Male | Prostate Cancer, Melanoma | 3 | 3 wk | 34.7 (< 2.9 eight days following first dose methylprednisolone) |

| Case 6 | 67 | Male | Right Forearm Melanoma | 3 | 18 wk | NA |

| Case 7 | 55 | Male | Back Skin Melanoma | 4 | 4 wk | 97.4 |

A 63 years old female with history of melanoma of the nasal mucosa presented with non-bloody diarrhea six weeks after starting ipilimumab. She was empirically treated with oral prednisone, but had symptom recurrence with steroid tapering. Colonoscopy showed diffuse mucosal erythema and ulcers with pathology significant for cryptitis (Figure 1). The patient’s course was further complicated by a perirectal abscess. The patient underwent drainage of the abscess and began treatment with budesonide (12 mg daily) with improvement of her symptoms within two days. She also received imatinib (400 mg twice daily) for her c-KIT mutant mucosal melanoma with significant anti-tumor response without reactivation of colitis symptoms.

A 38 years old male with a history of melanoma of the back developed loose non-bloody bowel movements approximately four weeks after starting ipilimumab. Colonoscopy was unrevealing and the patient was treated symptomatically with loperamide (Figure 2). Upon further workup, the patient was found to have a Group G Beta-Hemolytic Streptococcus bacteremia. Treatment of the underlying bacteremia resulted in resolution of the patient’s diarrhea.

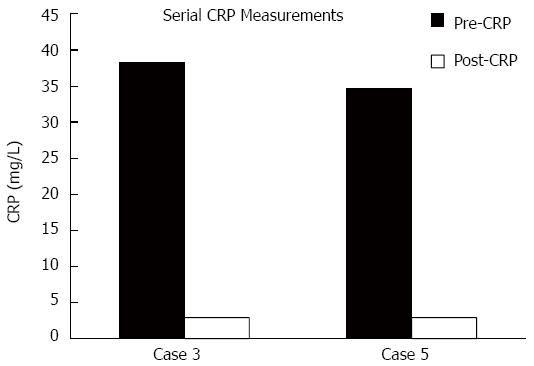

A 71 years old female diagnosed with facial melanoma began experiencing softer and more frequent stools five weeks after her first dose of ipilimumab. Colonoscopy revealed ulcers with no evidence of bleeding throughout the colon (Figure 3). She was started on budesonide (3 mg daily) and later switched to prednisone (60 mg twice daily). The patient’s symptoms improved only temporarily; few weeks later she developed bloody diarrhea. She was transitioned to methylprednisolone (60 mg twice daily) and showed no improvement after four days. She received two infusions of infliximab at 5 mg/kg spaced two weeks apart. Within four weeks of the first infliximab infusion the patient’s symptoms had resolved. C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were noted to decrease from 38.3 mg/L to < 2.9 mg/L ten days following the first infliximab infusion.

A 44 years old female with right inguinal melanoma developed nausea, fevers, and loose bowel movements nine weeks after her first dose of ipilimumab. A colonoscopy confirmed the diagnosis of colitis revealing loss of vascular pattern and mucosal friability. Pathology revealed evidence of colitis with destructive cryptitis and crypt microabscesses. She was started on prednisone with a two week taper and experienced improvement of her symptoms.

A 66 years old male with history of prostate cancer and melanoma began experiencing abdominal pain and diarrhea, which progressed to bright red blood per rectum, three weeks after his first dose of ipilimumab. Colonoscopy was significant for mucosal friability and multiple shallow punctate ulcerations, with pathology further confirming colitis. The patient experienced complete symptom resolution after only one day of treatment (methylprednisolone 85 mg daily). He was transitioned to oral steroids with a subsequent four week taper with no recurrence of symptoms. CRP levels were observed to decrease from 34.7 mg/L to < 2.9 mg/L eight days after his first dose of methylprednisolone.

A 67 years old male diagnosed with melanoma of the right forearm started having loose non-bloody bowel movements eighteen weeks after his first dose of ipilimumab. Colonoscopy showed evidence of colitis and pathological findings of increased inflammation and rare acute cryptitis. The patient was originally started on Budesonide 9 mg daily, but later switched to prednisone 100 mg daily after colonoscopy findings. The patient’s symptoms gradually abated.

A 55 years old male melanoma of the back presented with cramping abdominal pain associated with diarrhea four weeks following his first dose of ipilimumab. Multiple bland based ulcers were noted extending from the rectum to the ileum and pathology was consistent with acute colitis. The patient was originally started on prednisone 100 mg daily and later switched to methylprednisolone 100 mg twice daily when symptoms persisted. After three days of no improvement and progression of symptoms to bloody diarrhea, he was administered two doses of infliximab (5 mg/kg) two weeks apart. The patient noted near complete symptom resolution two weeks following the first infliximab infusion.

The majority of chief complaints were composed of diarrhea, fever, rash, abdominal pain, nausea and occurred three to eighteen weeks after initiation of ipilimumab (mean, 7 wk; following one to four doses of ipilimumab). Colonoscopy findings were consistent with those of colitis, including mucosal erythema, ulcerations, loss of vascular pattern, granulations, and friable mucosa. Common pathological observations on biopsy were granulomas, cryptitis, and crypt abscesses. Time to symptom resolution was noted to be variable (ranging from 1 d to 4 wk after initial treatment). CRP levels were elevated in all cases when measured, with normalization noted when measured serially post treatment in two of the cases. Two of the seven patients received infliximab infusions for treatment of their underlying colitis.

With the introduction of anti-CTLA-4 agent ipilimumab irAEs involving the digestive tract have become legitimate concern. Decision algorithms based on symptom grade have been developed to aid in the management of such toxicities, but much is to be elucidated. Although corticosteroids are recommended for moderate to severe symptoms, optimal dosing needs clarification. Management guidelines recommend starting prednisone or its equivalent (0.5 mg/kg/d for moderate and 1-2 mg/kg/d for severe enterocolitis), but case reports and trials have a myriad of steroid administration patterns. Furthermore, extended release formulations of the steroids have been developed, which have yet to be studied in such patients.

At our institution, cases of suspected ‘IpiColitis’ undergo colonoscopy with biopsies. We feel that colonoscopy is warranted early to confirm diagnosis. While clinical course may support the diagnosis of ipilimumab associated colitis, it is not sufficient, thus requiring tissue biopsy for confirmation. Once confirmed and infectious etiologies are ruled out, patients are started on prednisone (1 mg/kg/d). Simultaneously, patients are checked for tuberculosis and hepatitis B infections in preparation for possible future anti-TNF therapy. Intravenous steroids (1 mg/kg/d) are reserved for more persistent cases. If symptoms continue three to five days following intravenous steroid treatment, two doses of infliximab (5 mg/kg/dose) are administered two weeks apart with coinciding steroid taper. Patients are followed clinically and treatment success is based on resolution of the patient’s presenting symptoms and diarrhea. Repeat colonoscopy is not routinely conducted to confirm treatment response.

Phase 2 trials have shown no benefit of prophylactic budesonide use in the prevention of ipilimumab induced colitis[7]. To date we lack predictive and prognostic factors of severity of the immunological side effects prior to initiating ipilimumab therapy[8]. CRP, being a marker of acute inflammation, was noted to be elevated in all cases. The degree of elevation did not correlate to symptom severity, and did not serve as a surrogate indicator for the requirement of anti-TNF agents. In cases where CRP was checked after treatment, normal levels were noted, creating future interest in following this lab value as a measurement of treatment response (Figure 4). In Case 3, CRP levels were checked ten days following the first dose of infliximab and noted to have normalized. Similarly, in Case 5, CRP levels were noted to have normalized eight days following first dose of methylprednisolone.

With no definitive preventive strategy, and no predictive and prognostic factors, the physician has to assess disease severity and adjust medical treatment based on patient’s symptoms and the colonoscopy findings. Before attributing the diarrhea to ipilimumab, an infectious work-up should be done, including infectious enterocolitis and extra-intestinal infections, as illustrated by our patient diagnosed with Group G Beta Hemolytic Streptococcus bacteremia. The differential diagnosis of colitis remains broad and can arise from infectious pathogens, such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Clostridium difficile. Immunocompromised individuals are more susceptible to colitis due to cytomegalovirus infections. Ischemic changes can also result in colonic inflammation representative of colitis. Furthermore, microscopic forms of colitis exist, including lymphocytic and collagenous forms[9].

Cases non-responsive to steroids will often proceed to a trial of anti-TNF agents such as infliximab. This monoclonal antibody has an established use in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, and builds much of the foundation of how we treat steroid resistant immune-mediated colitis. While endoscopic findings have been correlated with more clinically aggressive forms of Crohn’s disease, further data and more rigorous studies are required to make such a correlation in ipilimumab-induced colitis[10]. Endoscopy is indicated in those patients whose symptoms are severe or refractory to oral steroids. The use of early endoscopy, its associated findings, and treatment implications are yet to be studied.

Case 1: 63 years old female with history of melanoma of the nasal mucosa presented with non-bloody diarrhea six weeks after starting ipilimumab.

Case 2: 38 years old male with a history of melanoma of the back developed loose non-bloody bowel movements four weeks after starting ipilimumab.

Case 3: 71 years old female diagnosed with facial melanoma began experiencing softer and more frequent stools five weeks after her first dose of ipilimumab.

Case 4: 44 years old female with right inguinal melanoma developed nausea, fevers, and loose bowel movements nine weeks after her first dose of ipilimumab.

Case 5: 66 years old male with history of prostate cancer and melanoma began experiencing abdominal pain and diarrhea, which progressed to bright red blood per rectum three weeks after his first dose of ipilimumab

Case 6: 67 years old male diagnosed with melanoma of the right forearm started having loose non-bloody bowel movements eighteen weeks after his first dose of ipilimumab.

Case 7: 55 years old male melanoma of the back presented with cramping abdominal pain associated with diarrhea four weeks following his first dose of ipilimumab.

Abdominal pain, nausea, fever, loose stools, diarrhea, bloody bowel movements.

Infectious colitis (E. coli, C. difficile, Salmonella, CMV), Microscopic colitis, Viral Gastroenteritis, Ischemic colitis.

Elevated CRP levels [range: 34.7 mg/L to 137 mg/L (Normal: < 2.9 mg/L)].

Colonoscopy revealing mucosal erythema, ulcerations, loss of vascular pattern, granulations, and friable mucosa

Pathological findings from colonic biopsies revealed granulomas, cryptitis, and crypt abscesses

Case 1: Treated with budesonide 12 mg daily.

Case 2: Symptomatic treatment with loperamide.

Case 3: First treated with budesonide 3 mg daily, later switched to prednisone 60mg twice daily. Steroids later changed to intravenous methylprednisolone 60mg twice daily, and finally received two doses of infliximab (5 mg/kg) spaced two weeks apart.

Case 4: Treated with prednisone.

Case 5: Methylprednisolone 85 mg daily.

Case 6: Budesonide 9 mg daily, followed by prednisone 100 mg daily.

Case 7: Prednisone 100 mg daily, later switched to methylprednisolone 100 mg twice daily, and ultimately treated with two doses infliximab (5 mg/kg) two weeks apart.

To date, we lack biomarkers that help predict the severity of irAEs or help determine patient’s treatment response to steroid treatment.

Immune-regulated adverse effects (irAEs) are thought to be those effects due to the T cell activation and immune up-regulation caused by ipilimumab.

This report not only represents the largest single institution case series of ipilimumab associated colitis, but also outlines our evaluation methods, treatment regimens, and outcomes of our patients. Furthermore, the authors suggest the use of serial CRP measurements as a possible surrogate biomarker to treatment response.

This article applies a retrospective case series review of those patients who developed gastrointestinal symptoms in the setting of receiving ipilimumab.

P- Reviewer: Forde PM S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711-723. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10799] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11094] [Article Influence: 792.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yang JC, Hughes M, Kammula U, Royal R, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, Suri KB, Levy C, Allen T, Mavroukakis S. Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA4 antibody) causes regression of metastatic renal cell cancer associated with enteritis and hypophysitis. J Immunother. 2007;30:825-830. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 518] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 519] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hanaizi Z, van Zwieten-Boot B, Calvo G, Lopez AS, van Dartel M, Camarero J, Abadie E, Pignatti F. The European Medicines Agency review of ipilimumab (Yervoy) for the treatment of advanced (unresectable or metastatic) melanoma in adults who have received prior therapy: summary of the scientific assessment of the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:237-242. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Graziani G, Tentori L, Navarra P. Ipilimumab: a novel immunostimulatory monoclonal antibody for the treatment of cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2012;65:9-22. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 93] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Available from: http://www.hrc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/CTCAE%20manual%20-%20DMCC.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Treatment and side effect management of CTLA-4 antibody therapy in metastatic melanoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:277-286. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Weber J, Thompson JA, Hamid O, Minor D, Amin A, Ron I, Ridolfi R, Assi H, Maraveyas A, Berman D. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II study comparing the tolerability and efficacy of ipilimumab administered with or without prophylactic budesonide in patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5591-5598. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 430] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pagès C, Gornet JM, Monsel G, Allez M, Bertheau P, Bagot M, Lebbé C, Viguier M. Ipilimumab-induced acute severe colitis treated by infliximab. Melanoma Res. 2013;23:227-230. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 95] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sherid M, Ehrenpreis ED. Types of colitis based on histology. Dis Mon. 2011;57:457-489. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Allez M, Lemann M, Bonnet J, Cattan P, Jian R, Modigliani R. Long term outcome of patients with active Crohn’s disease exhibiting extensive and deep ulcerations at colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:947-953. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |